中国或提前进入碳排放“峰值平台期”(中文)

要实现“十四五”目标,中国必须严格遏制近期出现的碳排放增长。如果做的好,甚至可能提前推动碳排放“达峰”。

For China to reach the targets it has set in the 14th Five Year Plan, it must strictly curb the recent growth in carbon emissions. Interestingly, this could cause the ‘peaking plateau’ to start sooner than many had expected.

There is much interest in China’s greenhouse gas emissions. Even though China’s per capita emissions are still lower than most developed countries, its total emissions are more than the USA and Europe combined, and they continue to grow. A few weeks ago, UN Secretary-General Guterres warned of a ‘code red’ for humanity, following the IPCC report on climate science which shows unequivocal human influence on the climate, leading to increasingly disastrous consequences. Global efforts to curb climate change will be discussed in Glasgow in November, so it is a good time to take stock of what’s happening in China.

In this article, I take a look at China’s emissions targets, estimates of actual emissions, some of the drivers behind emissions and efforts to curb them, in order to understand whether China is likely to meet the climate targets it has set and to get a sense of how emissions may develop between now and 2030. I conclude with some proposed next steps in China and for western actors engaging with China.

Targets and emissions

The most important near-term climate targets are those in the 14th five-year plan, mainly to reduce CO2 emissions per unit of GDP by 18%. Aside from the question of how ambitious that target is, it is worth emphasizing that this target is one of only eight ‘binding’ targets in the entire five-year plan. Most of the other binding targets also relate to the environment. This highlights the level of priority the central government attaches to the climate targets and should give us some confidence that all efforts will be made to achieve them.

The mid-term target is to peak carbon dioxide emissions before 2030. I underline ‘before’, because many prominent international media, and even some Chinese state media, have incorrectly used the word ‘by’ 2030. I have personally clarified this question with the Chinese government. President Xi’s pledge on 22 September 2020 was for carbon to peak before 2030. That was correct, and this target remains unchanged. That means the peak must be achieved any time between now and 2029, so emissions should be declining in 2030 and onwards.

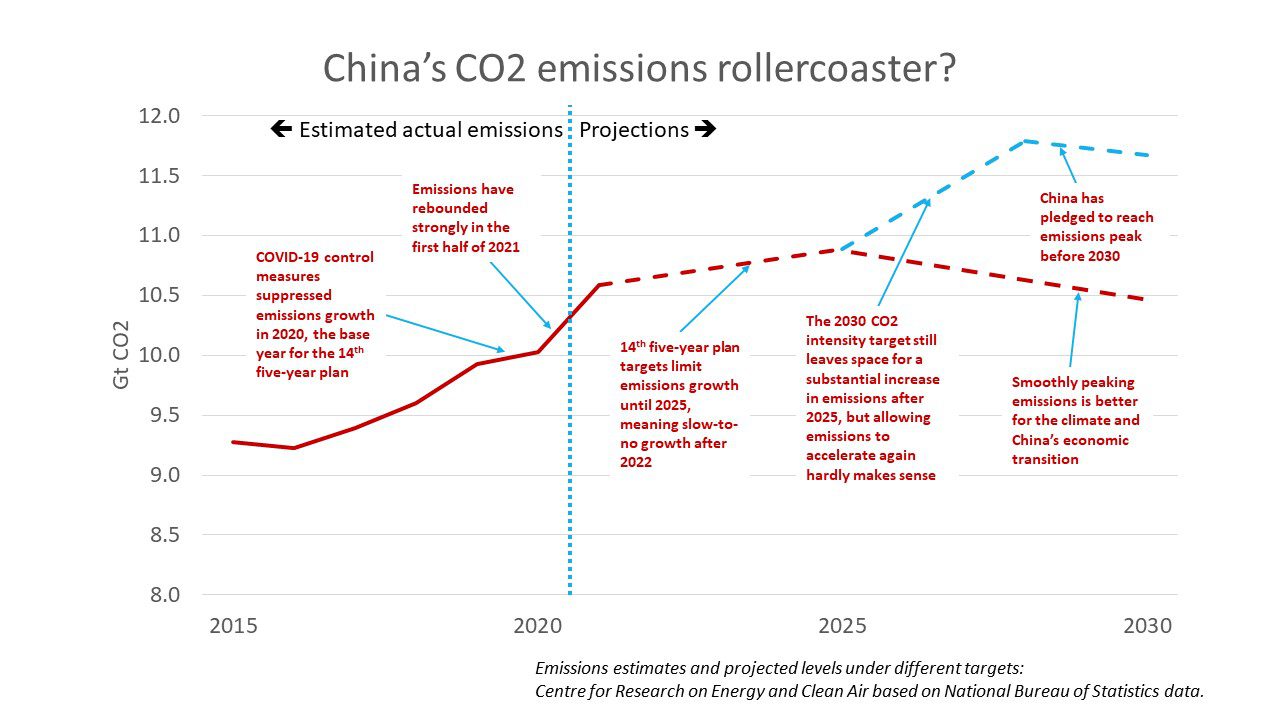

Concerningly, emissions appear to have risen quickly in 2020 and the first half of 2021, making the 2025 target harder to achieve. China, like many other countries, doesn’t regularly release official figures on actual carbon emissions. However, a recent report by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air analyzed various industrial and energy-related statistics, and estimated that China’s CO2 emissions have risen by about 9% year on year in the first half of 2021, and the full year could easily see a 5% increase. Such a rapid increase in emissions must be quickly curbed if the 14th five-year plan targets are to be met.

What’s happening in China?

The recent increase in emissions highlights the challenges of actually bringing emissions under control. A large share of China’s economy relies on carbon-intensive industries, and there remains downward economic pressure due to covid and difficulties in international relations. Despite the clear warnings from the central government, many provinces still try to achieve economic growth in ‘business as usual’ sectors such as coal-fired power generation and steel production.

Another difficulty lies in the level of public awareness of climate science, which is much lower than in Europe. Many people I speak to, some of whom are well educated and in important positions, have misconceptions about climate change reminiscent of climate deniers in the USA and Europe (e.g. it’s not a big problem, it’s not caused by humans, the science isn’t clear). Some even believe that their leaders have been misled by foreigners who want to keep China from developing. Few have a solid understanding of what true low-carbon development looks like. As a result, there continues to be a low level of buy-in, and limited capacity, among key stakeholders across society, including local government, business, and the broader population.

The result is a major tug of war between the central government, and some provinces and sectors. This explains recent actions by the central government and leadership – they have been very actively following up on the carbon peaking efforts, applying some of the most powerful instruments available to address the problem. Some of the most important tools to curb emissions in the immediate term include affirmation of top-level commitment, suspending approvals of high emissions projects, central environmental inspections, and the rapid roll-out of new policies and regulations:

- Top-level commitment: This year, President Xi made several speeches in which he clearly emphasized the urgency of controlling emissions. At the end of April, he said: “high emissions projects which don’t meet requirements must be resolutely taken down”. Then in May, a new high-level “leaders’ group for the works of carbon peaking and carbon neutrality” was established to coordinate the efforts, led by vice-premier Han Zheng, and including leaders of all key ministries. Soon after at the end of July, President Xi said “everyone must get on the same page” to achieve carbon peaking, probably referring to the divergence between central instructions and the actions by certain provinces and sectors. Just this week, a central government team was established to measure actual emissions, signaling that it won’t tolerate provinces or sectors to fudge emissions data.

- Suspending approvals: In August, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) released a progress report on the control of energy consumption and energy intensity of each province for the first half of 2021. Nine provinces were warned for seriously deviating from their targets. For those, NDRC required suspension of new high emission projects in 2021, except those being part of ‘key national planning’. NDRC also issued another notice targeting major industrial parks along the Yellow River, which counts many carbon-intensive areas. It was required to re-assess and ‘correct’ all the existing and proposed projects with high emissions.

- Central Environmental Inspections: Powerful teams of environmental officials, prosecutors, and party disciplinary inspectors (anti-corruption watchdogs) have been deployed since 2018 to enforce environmental policy and regulations, with a focus on provincial leaders and large state-owned enterprises. In January this year, it emerged that the National Energy Administration, a central government agency, had received a ‘Central Environmental Inspection’ visit, and was publicly criticized for not taking the energy transition seriously enough. In July, MEE clarified that carbon peaking will be prioritized in the current and future work of the inspection teams and that high emission projects shall be strictly controlled. Provincial and SOE leaders play a key role in the planning and approvals of high emissions projects. In the Chinese political context, these inspections are an extremely effective tool.

- New policies and regulations: In July, China’s emissions trading system conducted its first trades for the power sector. Over the coming years, other high emissions sectors will be included. Also in May, MEE issued a guiding opinion on which specifies how high emissions projects must be prevented ‘at the source’. MEE also issued a policy document in July, which specified that carbon emission must be included in environmental impact assessments. The use of green finance is also increasingly used to support climate transition. In October 2020, MEE together with the other four ministries jointly issued a Guiding Opinion on Promoting Climate-Related Investment and Financing. Earlier this year, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) together with other ministries revised China’s green bonds catalogue, excluding fossil fuel-related projects. Then in July, PBOC issued a disclosure guidance on environmental information and a financing standard on environmental equities to be applied by financial institutions.

For China’s overseas investments, the picture seems brighter – last year saw more BRI investments in non-fossil than fossil fuel projects, and the first half of 2021 saw no new investments in overseas coal power projects. A series of policy documents have been issued on green finance and greening overseas investments, including the “Green Development Guidelines for Overseas Investment and Cooperation”, which encourages Chinese businesses to integrate green development throughout the whole overseas investment process, encouraging renewable energy as key areas for investment. More such policies are expected to follow.

China’s emissions in the decade to 2030

The upshot of all this, is that despite all the challenges, it appears the approval of new high emissions projects is being brought under control, and at a minimum we should see a slowdown in the growth in emissions.

Perhaps counterintuitively, it also seems possible that emissions may flatten from 2022 onwards, potentially starting the so-called ‘peaking plateau’ earlier than most of us had anticipated. This is a calculated estimate, based on the following assumptions:

- Economic growth of 8% in 2021 (boosted by recovery from the covid-induced dip in 2020), and 5.5% in the following years until 2025 – consistent with the ambition for “high-quality economic growth;”

- The energy intensity targets and non-fossil targets (13.5% reduction and 20% of total energy consumption) imply an actual CO2 intensity reduction of about 19.3%;

- To meet the CO2 intensity target for 2025 under the assumed level of GDP growth, overall CO2 emissions can only grow by 8% over the entire five-year period;

- In 2021 alone, China’s CO2 emissions grow by about 5-6%, effectively consuming most of the ‘room’ to grow emissions in the entire 14th five-year plan and leaving about 2% of potential emissions growth for the remaining four years from 2022 to 2025.

In theory, emissions could start to grow again in the period between 2026 – 2029, but this hardly makes sense given the objective to be carbon neutral by 2060. It would be better for the climate, and for a smooth economic transition in China, if emissions would gradually enter a decline in that period (see the red dotted line in the graph above). The lower emissions trajectory also roughly corresponds with the messages from Prof He Jiankun of Tsinghua University, who led the study underpinning China’s carbon neutrality pledge for 2060. In his words, China’s emissions should enter a ‘peaking plateau’ around the middle of this decade and enter a ‘steady decline’ before 2030.

Some ideas for the next steps

Needless to say, given the severity of the climate crisis, all countries need to make their best possible efforts to curb emissions. I have confidence that China’s central government will continue to make all efforts to curb emissions, and reach a peak in carbon emissions as soon as possible. On top of the powerful tools which are already being deployed (see above), a few more important approaches may be adopted, some of which have already been alluded to by officials in the Ministry of Ecology and Environment:

- Set absolute CO2 and/or GHG emissions targets for 2025 and 2030: The current intensity targets don’t provide certainty for the climate, because under high GDP growth scenarios, emissions could continue to grow. Absolute targets would also be easier to understand, be more aligned with international practice, and be easier to break down across provinces and sectors in China.

- Build climate awareness and capacity: Government, scientists, and media should keep sending clear and unified messages about climate science, clearly highlighting the urgency and the risks to China and the world. For example, when extreme weather events such as heat waves, floods and droughts occur, media should refer to the language used in scientific climate reports such as the recent IPCC AR6, and when available, provide coverage of studies that examine linkages between specific events and climate change. Local government and SOE leaders play an especially important role in the transition – their capacity to make the right decisions for the climate should be quickly ramped up. It should also be considered to require provinces and sectors to regularly disclose actual GHG emissions, to achieve greater transparency and broader stakeholder participation.

- Make greater use of the legal system: To avoid ‘campaign-style’ climate actions, provide long-term certainty, and provide a strong legal basis for the climate transition, climate considerations should be further integrated into the legal system. A dedicated climate change law should be drafted, and other key legislation should incorporate climate (Energy Law, environmental permitting system, etc). China’s Supreme People’s Court has made it clear that climate cases are welcome. China has a special department of public interest prosecutors who have brought thousands of cases for the environment in recent years – they could also be deployed to bring climate change cases. Even in the absence of a climate law, they could challenge illegal approvals of new high emissions projects and plans, and bring legal actions following up on the findings of the Central Environmental Inspections.

How to deal with China ahead of COP26 in Glasgow?

Given the complex geopolitical situation today, combined with China’s domestic climate dynamics, there is a risk that aggressive international efforts pushing China to accelerate its climate ambitions, even well-intended ones, could backfire if they put China’s leadership in an awkward position. The central government is already pushing very hard in the face of a low level of understanding and low buy-in among key stakeholders at home, and China’s leadership must always act in China’s interests. It can’t be perceived as caving into Western pressure.

On top of that, climate is one of the only areas in which the USA, Europe and China continue to have positive cooperation. Climate cooperation is a pillar of global peace. It would be unfortunate and potentially very dangerous, if geopolitical tensions would start to spill over and undermine global climate efforts.

Therefore, in the runup to COP26 in Glasgow, the best thing western government leaders can do to accelerate climate action in China and around the world, is to lead by example, encourage global ambition and action, and strike a constructive and cooperative line with China. Western leaders should continue to push hard on the climate transition in their own countries, and deliver on their previous commitments, especially to make available 100 bn USD per year to support the climate transition in the developing world.

China has lived up to its climate commitments so far, and is expected to submit its revised Nationally Determined Contribution ahead of COP26. If China could be convinced to further step up its climate commitments, it would have to be in the context of international cooperation.

The views expressed in this op-ed are those of the author and not necessarily those of CCICED.